Hello, Welcome.

We’re all journalists now. Anybody with a smart phone can record pictures and sound that might, within hours, be transmitted around the world; not only on social media but in newspapers and on TV.

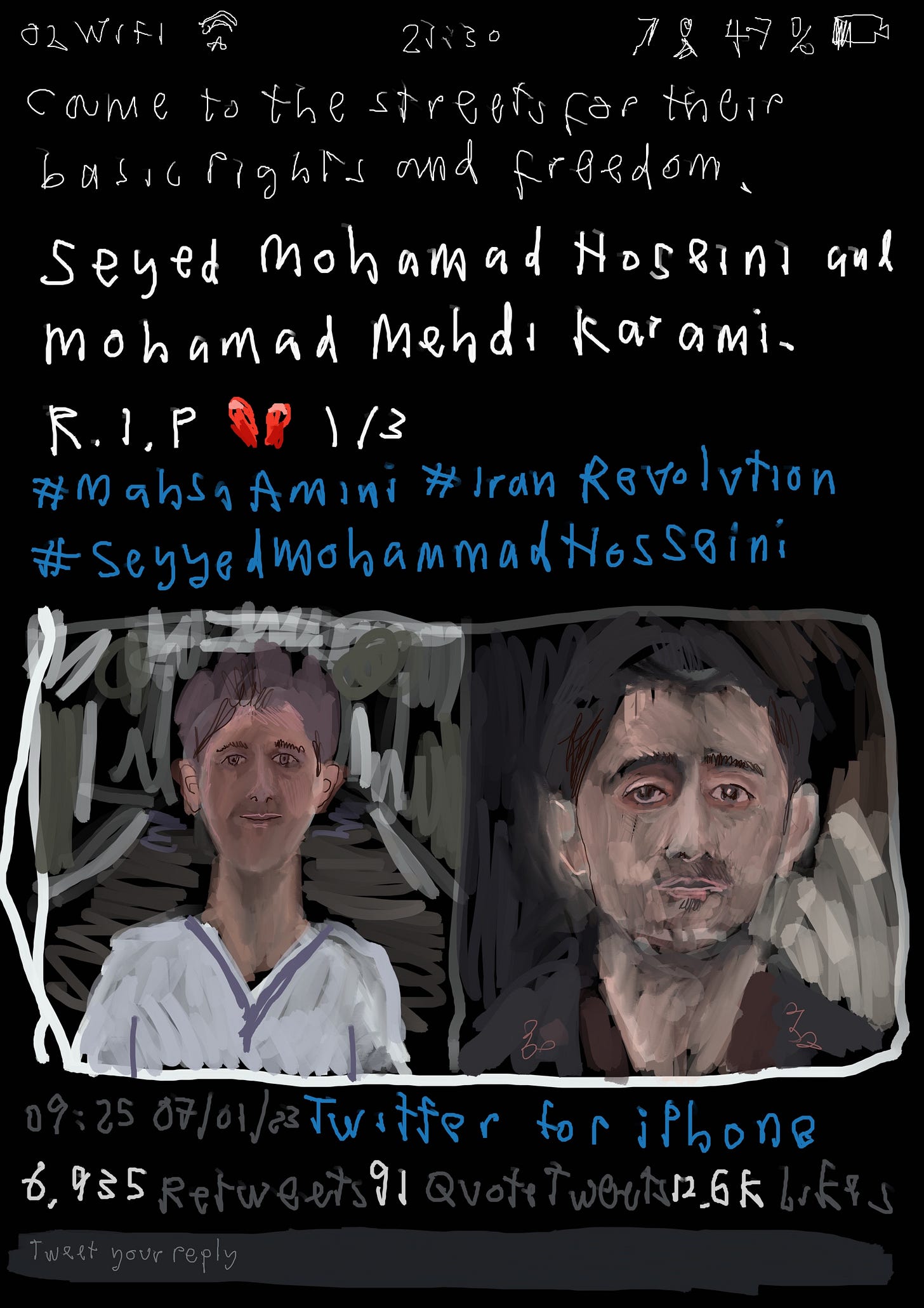

I could give you a zillion examples, but here’s a drawing I made of somebody’s tweet. I don’t know who tweeted it. (I’ve deleted my Twitter account, and the app too.)

I saw it because someone I know - someone who was born in Iran - retweeted it. It’s about two men executed in Iran, and for some reason at that moment I felt myself inclined to commemorate the men with a drawing:

Even by drawing a picture of someone else’s retweet, and sharing the picture here, I’m taking part in some kind of journalism.

Actually, I’d go further: you’re a journalist even if your output doesn’t get picked up and shared.

Journalism starts when somebody writes in a journal. Take Anne Frank: she didn’t write her diary for publication but after she’d gone her account of life as a Jewish girl in Nazi-controlled Amsterdam became an international best-seller, shedding more light than any number of newspaper reporters.

If I’m right about this, then others who deserve consideration as journalists include poets, novelists, cartoonists, comedians, illustrators and street performers, because in some places being a conventional journalist is simply too dangerous. I look forward to writing about some of these variants here. Doing so might inspire me to use some of their approaches - and inspire you, too.

But there’s a downside.

The same economic and technical forces that have turned us all into kind-of journalists have wreaked havoc on the business model of journalism-as-we-knew-it.

Hello. I’m John-Paul.

I’m a writer, artist and performer who also teaches those things. My books include How To Change The World, A Modest Book About How To Make An Adequate Speech, and (the latest) Psalms for the City. Between them, my books have been published in 16 languages. But my writing career started in journalism.

Having studied English literature at university, I wanted to be a poet. There didn’t seem much prospect of making a living that way, and journalism looked then like it might (hah!).

For a long time, my idea of a perfect job in journalism was to write for a literary publication. I still like that idea. Now that I also make art for a living, I fantasise about providing illustrations to them too. Here’s a totally fake cover of the London Review of Books I created recently, using one of my drawings of Hampstead Heath:

If that makes me seem like a hopeless dreamer… For many years I was a feature writer and editor on The Financial Times and The Sunday Times (of London).

I was lucky to cover a huge range of topics, using many approaches. I wrote interviews, news stories, film reviews, stories that were meant to be funny and others that were tragic.

Sometimes I went under cover, sometimes I worked openly alongside a photographer. Since then, I’ve also run a podcast and done reportage using illustrations.

I mention these things only because you might want to know that you are reading somebody who does have some experience.

I write fast, and I always worked hard. Once, the FT sent me to New York, where in the course of less than a week I researched and subsequently wrote a total of nine longish feature stories. But I sometimes spent several months on a single story. To be clear: it was never the only thing I worked on over that period, but if you were to add up the hours, you’d find that I spent many days on that one story.

Lucky me, you might say - and I would agree.

I do agree.

I agree now, and I would have agreed then. I thought I had the best job in the world. I was so lucky.

But the internet gradually ate into the business model. Readers became less willing to pay. And the FT decided it was no longer possible to employ a full-time feature writer on the Saturday magazine. I was offered alternative positions, or voluntary redundancy. I took the money.

I moved to the The Sunday Times, with a contract to write a certain number of articles each year - some for the magazine, some for the main paper. For a while it felt as if I’d lucked out again: I could work from home, which was convenient because I’d recently become a father.

I continued to work hard - and was paid extra for work that surpassed my contract - but without a full-time job I had no health, holiday or pension benefits. And gradually, as my contract was renegotiated over the years, the fee for stories went down, not up. Additionally, frighteningly, the contract was reduced to a smaller number of stories. I could do more, but there was no guarantee, and frequently the editors said no to my ideas.

Imperceptibly, I became someone who worries about money from one week to the next. This would eventually contribute to a breakdown that landed me in psychiatric hospital. I’ll probably write about that occasionally, because the breakdown - and subsequent recovery - had a huge effect on me.

Of course, the same was happening to people in all kinds of other industries, and my point is not (now, anyway) to indulge in self-pity. Instead, I want to draw your attention to a bigger, more significant problem: the quality of journalism is eroded if it’s not adequately funded.

People cut corners. In journalism, the ways this can happen include: shrinking the physical size of a publication, or the time given to a broadcaster’s output; reducing its scope (fewer specialist reporters); paying fewer editors to read more words, more quickly (more mistakes); replacing experienced staff with juniors (less institutional memory of internal and external events); doing interviews remotely, instead of in person, to save the time and money involved in travel; not checking what people tell you by asking secondary sources (fake news); and avoiding altogether stories that might cause expensive legal difficulties (tame journalism).

None of these budgetary manoeuvres is new. And none of them, on its own, invalidates what journalists produce. But taken as a whole they shift the quality from one end of the spectrum (essential reading/listening/viewing) towards the other (don’t bother). Consciously or unconsciously, readers and viewers pick up on that.

A few years ago, I met one of my heroes: a journalist who had published many books and was once - long, long ago - editor of The Sunday Times magazine. At one point, he mentioned that the perks of his job, back then, had included a chauffeur-driven car. I was amused, then outraged, that journalism of exactly the kind I had done was once so richly funded.

Time to wail, and gnash the teeth?

Not necessarily. You don’t need to be a Marxist revolutionary to see that a journalist who is driven around by a chauffeur will be limited in his outlook and his capacities, just as much as a journalist who is short of cash. The limits are different, but they’re real. And there is value in that diversity - real value. People with different life experience have different stories to tell, and being exposed to some of that variety, at least occasionally, enriches us all. We don’t have to agree with it, but it’s salutary to know what other people think, and what they go through.

We need variety. We need outsiders, newcomers, beginners and part-timers who are finding a voice, just as we need established writers with the kind of support that enables them to do great work.

Hence this newsletter, Think Like A Journalist.

The plan is to write about journalism, in the widest sense, and also to do some journalism myself.

I’m excited about both.

I want to share ideas and inspiration so that you can go forth and practice journalism in the way that’s most satisfying to you; and I want to write stories that matter to me.

Since leaving full-time journalism more than a decade ago, I’ve diversified by writing books, training in theatrical improvisation, doing paid illustration - and a fair bit of teaching. I love this variety. But I’ve lost one thing: the feeling that comes from being a writer working for a particular publication that really wants to publish the stories I want to write.

For more than 20 years, I’ve posted thousands of stories and images to my own website (including many of the links immediately above). But the internet is changing all the time. Most people experience it through one of a small number of walled gardens - Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and so on. These walled gardens don’t want users to leave, so posts with links to external websites like mine get little visibility.

For 18 months, I’ve followed Substack with interest, subscribing to several newsletters, both free and paid. Substack seems to provide a welcome space somewhere in between social media and a private website. I like the way Substack encourages writers to feel supported, building warm, interactive relationships with readers in a semi-private space.

This newsletter, Think Like A Journalist, is mine. I do the work and set the direction. But your ideas and encouragement are gratefully received. And if you subscribe I hope you feel that you have a small stake in what I produce.

Stay up-to-date

You won’t have to worry about missing anything. Every new edition of the newsletter goes directly to your inbox.